neuroscience-ai-reading-course

Transferring pre-trained LMs

Aim of the paper:

Tackling the problem of transferring an existing pre-trained model from English to other languages under a limited computational budget. Furthermore, evaluating the models on six languages, the authors demonstrate that their models are better than multilingual BERT on two zero-shot tasks*: natural language inference and dependency parsing**.

(*zero shot tasks → a problem setup in machine learning, where at test time, a learner observes samples from classes that were not observed during training, and needs to predict the category they belong to.)

(**dependency parsing → task of recognizing a sentence and assigning a syntactic structure to it. The most widely used syntactic structure is the parse tree which can be generated using some parsing algorithms.)

Introduction:

Available multilingual pre-trained models:

(1) The multilingualBERT (mBERT) that supports 104 languages,

(2) Cross-lingual language model (XLM; Lample & Conneau, 2019) that supports 100 languages, and

(3) Language Agnostic Sentence Representations (LASER; Artetxe & Schwenk, 2019) that supports 93 languages.

Among the three models, LASER is based on neural machine translation approach and strictly requires parallel data to train.

Bilingual Pre-trained LMs:

A pre-trained LM typically performs the following computations:

(i) transform a sequence of input tokens to contextualized representations

(ii) predict an output word yi at ith position

Given an English pre-trained LM, we want to learn a bilingual LM for English and a given target language l under a limited computational resource budget.

3 steps:

- Initialize target language word-embeddings E(l) in the English embedding space such that embeddings of a target word and its English equivalents are close together.

- Create a target LM from the target embeddings and the English encoder Ψ(θ). We then fine-tune target embeddings while keeping Ψ(θ) fixed.

- Finally, we construct a bilingual LM of E(e), E(l), and Ψ(θ) and fine-tune all the parameters.

Initialising target embeddings:

The approach to learn the initial foreign word embeddings E(l) is based on the idea of mapping the trained English word embeddings E(e) to E(l) such that if a foreign word and an English word are similar in meaning then their embeddings are similar.

Represent each foreign embedding as a linear combination of English word embeddings.

Fine tuning target embeddings:

Replace English word-embeddings in the English pre-trained LM with foreign word-embeddings to obtain the foreign LM. Then fine-tune only foreign word-embeddings on target monolingual data.

Fine tuning Bilingual LM:

Create a bilingual LM by plugging foreign language specific parameters to the pre-trained English LM. The new model has two separate embedding layers and output layers, one for English and one for foreign language. The encoder layer in between is shared.

Then fine-tune this model using English and foreign monolingual data. Here, keep tuning the model on English to ensure that it does not forget what it has learned in English and can be used for zero-shot transfer.

Zero-shot Experiments:

BERT and RoBERTa as source models for building our bilingual LMs, named RAMEN.

RoBERTa is a recently published model that is similar to BERT architecturally but with an improved training procedure. RoBERTa is included in experiments to validate: with similar architecture, does a stronger pre-trained English model results in a stronger bilingual LM?

Models evaluated on two cross-lingual zero-shot tasks: (1) Cross-lingual Natural Language Inference (XNLI) and (2) Dependency Parsing.

Data:

6 target languages: French (fr), Russian (ru), Arabic (ar), Chinese (zh), Hindi (hi), and Vietnamese (vi). These languages belong to four different language families. French, Russian, and Hindi are Indo-European languages, similar to English. Arabic, Chinese, and Vietnamese belong to Afro-Asiatic, Sino-Tibetan, and Austro-Asiatic family respectively.

French and Russian, and Arabic can be regarded as high resource languages whereas Hindi has far less data and can be considered as low resource. WikiExtractor7 used to extract extract raw sentences from Wikipedias as monolingual data for fine-tuning target embeddings and bilingual LMs. No lowercase or removal of accents in data preprocessing pipeline.

Datasets used: XNLI dataset for classification task and Universal Dependencies v2.4 for parsing task.

Estimating Translation probabilities:

The vector e(s) of subword s is the weighted average of all the aligned word vectors e(wi) that have s as an subword.

Not all the words in the foreign vocabulary can be initialized from the English word embeddings. Those words are initialized randomly from a Gaussian N (0, 1/ $d^2$).

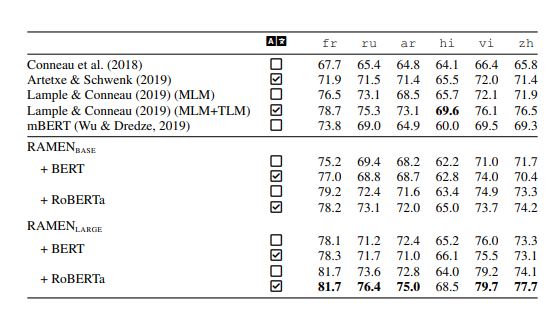

Result for Cross-lingual Natural Language inference:

Transfer results from BERT:

Initialized from fastText vectors, RAMEN_base, slightly outperforms mBERT by 1.9 points on average and widen the gap of 3.3 points on Arabic. RAMEN_base gains extra 0.8 points on average when initialized from parallel data. With triple number of parameters, RAMEN_large offers an additional boost in term of accuracy and initialization with parallel data consistently improves the performance.

Transfer results from RoBERTa:

With the same initializing conditions, RAMEN_base+RoBERTa outperforms RAMEN_base+BERT on average by 2.9 and 2.3 points when initializing from monolingual and parallel data respectively.

This result show that with similar number of parameters, our approach benefits from a better English pre-trained model. When transferring from RoBERTa_large, state-of-the-art results obtained for five languages.

Currently, RAMEN only uses parallel data to initialize foreign embeddings.

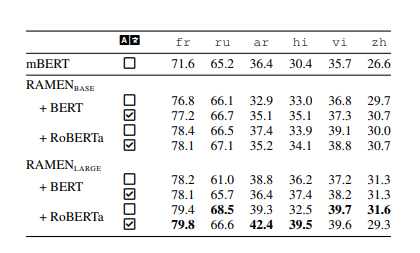

Result for Universal Dependency Parsing:

For the purpose of evaluating the contextual representations learned by our model, part-of-speech tags are not used. Contextualized representations are directly fed into Deep-Biaffine* layers to predict arc and label scores.

(* Timothy Dozat and Christopher D. Manning. Deep biaffine attention for neural dependency parsing. In ICLR, 2016.)

(Labeled Attachment Score (LAS) is a standard evaluation metric in dependency parsing: the percentage of words that are assigned both the correct syntactic head and the correct dependency label.)

Between mBERT and monolingually initialized RAMEN_base+BERT, the latter outperforms the former on five languages except Arabic. The largest gain of +5.2 LAS is observed for French. Chinese has +3.1 LAS.

With similar architecture (12 or 24 layers) and initialization (using monolingual or parallel data), RAMEN+RoBERTa performs better than RAMEN+BERT for most of the languages.

Arabic and Hindi benefit the most from bigger models. For the other four languages, RAMEN_large renders a modest improvement over RAMEN_base.